In

Sweden St. Lucia’s Day was formerly marked by some interesting practices.

It was, so to speak, the entrance to the Christmas festival, and was called

“little Yule.” At the first cock-crow, between 1 and 4 a.m., the

prettiest girl in the house used to go among the sleeping folk, dressed in a

white robe, a red sash, and a wire crown covered with whortleberry-twigs and

having nine lighted candles fastened in it. She awakened the sleepers and

regaled them with a sweet drink or with coffee, sang a special song, and was

named “Lussi” or “Lussibruden” (Lucy bride). When everyone was

dressed, breakfast was taken, the room being lighted by many candles. The

domestic animals were not forgotten on this day, but were given special

portions. A peculiar feature of the Swedish custom is the presence of lights

on Lussi’s crown. Lights indeed are the special mark of the festival; it

was customary to shoot and fish on St. Lucy’s Day by torchlight, the

parlors, as has been said, were brilliantly illuminated in the early

morning, in West Gothland Lussi went round the village preceded by

torchbearers, and in one parish she was represented by a cow with a crown of

lights on her head. In schools the day was celebrated with illuminations.

“What is the explanation of this feast of lights? There is nothing in the legend of the saint to account for it; her name, however, at

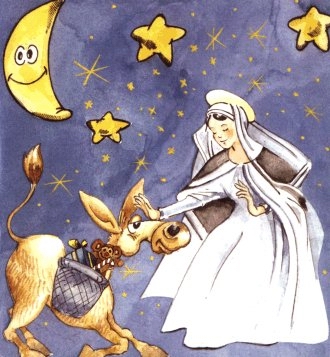

Swedish girl with

Lussi’s crown

once suggests lux—light. It is possible, as Dr. Feilberg supposes, that the name gave rise to the special use of lights among the Latin-learned monks who brought Christianity to Sweden, and that the custom spread from them to the common people. A peculiar fitness would be found in it because St. Lucia’s Day according to the Old Style was the shortest day of the year, the turning point of the sun’s light.

“In

Sicily also St. Lucia’s festival is a feast of lights. After sunset on the

Eve a long procession of men, lads, and children, each flourishing a thick

bunch of long straws all afire, rushes wildly down the streets of the

mountain village of Montedoro, as if fleeing from some danger, and shouting

hoarsely. “The darkness of the night,” says an eye-witness, “was

lighted up by this savage procession of dancing, flaming torches, whilst

bonfires in all the side streets gave the illusion that the whole village

was burning.” At the end of the procession came the image of Santa Lucia,

holding a dish, which contained her eyes. In the midst of the piazza a great

mountain of straw had been prepared; on this everyone threw his own burning

torch, and the saint was placed in a spot from which she could survey the

vast bonfire.